America, as a nation, adores fast food. The story of McDonald’s, brainchild of the McDonald brothers in California in the late 1940’s, then bought, franchised and expanded by Ray Kroc

in the 1950’s, can be read as a typically American story of starting from nothing and triumphing over the odds to achieve great success. The iconic styling of the restaurants, as well as McDonald’s symbiosis with the automobile, capture a particular moment in the American psyche, when all things were possible and bigger was better, in both tail fins and franchises.

Today, there are over 13,000 McDonald’s franchises, far outnumbering Burger King (7,000+) and Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and Wendy’s (about 6,000 each). This lovely map by Ian Spiro at fastfoodmaps.com maps fast food outlets in the U.S., and the numbers are truly staggering.

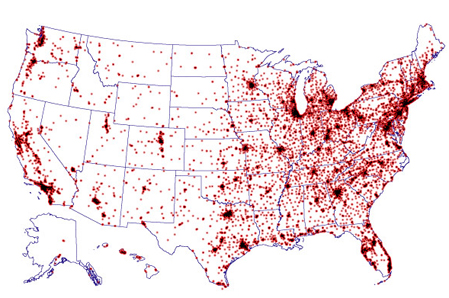

Here’s a map of just the McDonald’s:

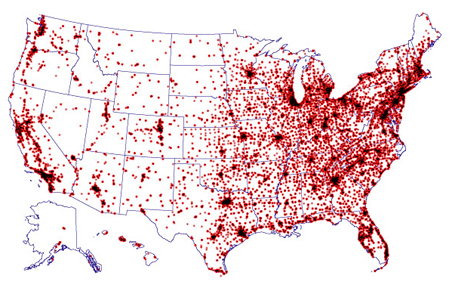

And another map of McDonald’s, Burger King, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, Wendy’s, KFC, Jack in the Box, Hardee’s, Carl’s Jr, and In-N-Out:

The map doesn’t even include the smaller chains like Roy Rogers, White Castle, Subway, Blimpie, Quiznos, Dunkin’ Donuts, Whataburger, or Chick-fil-A, or the slightly more upscale ‘fast casual’ of chains like Panera Bread or Chipotle. McDonald’s also has about 1,000 Canadian franchises, 10,500+ international franchises, and about 8,000 company-owned international locations worldwide.

With numbers like that, it’s not surprising that McDonald’s is the largest American purchaser of beef, potatoes, and pork, and the second largest of chicken, according to Eric Schlosser’s 2001 book, Fast Food Nation.

At this scale, McDonald’s purchasing guidelines have an enormous impact on their suppliers and the farmers who supply the food. The 2005 introduction of the fruit & walnut salad, part of an effort to provide more ‘healthy’ food choices, really shows the gargantuan effect McDonald’s has. Essentially overnight, since the introduction of the salad in 2005, McDonald’s has become the largest purchaser of apples in the U.S., over 54 million pounds a year.

As an article in the Guardian explains,

McDonald’s … now buys more apples than any other restaurant chain in the United States. And if the product … takes off, it has the potential to transform an entire agricultural industry. The chain’s influence could alter for ever the method and scale of production, the varieties of apple produced, and the rights of the thousands of workers who pick them, and not necessarily for the better.

Big retail buyers such as Wal-Mart and Safeway have already started this process. Experience in other sectors suggests that, at some stage, the balance of power shifts, and the buyer dictates the terms. Already, retailers demand an apple that is 3ins in diameter – the optimum size to maximise the number that can be displayed within a square foot, while remain appealing to the consumer.

The entry into the market of McDonald’s, which prides itself on the fact that its meals taste the same wherever you are in the world, will only accelerate this trend towards uniform mass consumption. The bigger a producer, the greater the likelihood that McDonald’s will want to do business with it because it will be able to provide everything the chain needs. “It will want large volumes of uniform apples that have to be the same variety and the same size,” says Desmond O’Rourke, economist and publisher of World Apple Report. ” And it wants to deal with large shippers who can produce those numbers.

Another article in the New York Times touches on the same problem: the increased vertical integration of the suppliers, and the increased scale and standardization necessary, are squeezing out the smaller growers. The article continues,

Other advocacy groups said that they were hopeful that McDonald’s would one day use its power not only to get better prices and greater supply, but also to change the way the produce industry operates – for the better. Ronnie Cummins, national director of the Organic Consumers Association, an advocacy group based in Little Marais, Minn., said he would like to see McDonald’s buy some organic products, which he believes are more healthful for consumers.

In a 2003 report on pesticides in produce, the Environmental Working Group, a public-policy outfit based in Washington, ranked apples as the third-most-contaminated produce group, after peaches and strawberries, in terms of pesticide residue. The findings were based on tests done by the Agriculture Department and the Food and Drug Administration from 1992 to 2001.

“McDonald’s could have a huge impact,” Mr. Cummins said. “They could be the company that changes agriculture toward a more organic and sustainable model.” It may sound far-fetched, but from a company that’s come a long way from the days of selling mainly hamburgers and fries, anything is possible.

What would a shift by McDonald’s towards organic apples, or organic potatoes and hamburger look like? The recent push by Wal-Mart towards stocking greater amounts of organic produce suggests that it wouldn’t really be all that different from the standard model, just with a bit fewer pesticides and drugs. Given the purchasers’ requirements of uniformity and scale, organic products destined for McDonald’s and Wal-Mart are still overwhemingly going to be produced by large growers and conglomorates via large-scale monocrop methods. Furthermore, an article from BusinessWeek in 2007 examines the ‘organic-ness’ of Wal-Mart and finds it lacking:

Now there are questions about whether “the Wal-Mart price” might come at a cost to organic foods. State officials in Wisconsin have launched an investigation into the retailer’s practices after complaints that Wal-Mart may be misleading consumers. A central question is whether signs on store shelves and banners above the shelves describe foods as “organic,” while the foods nearby do not qualify for the label, under federal guidelines.

Retailers and farmers involved in organic foods worry that giants like Wal-Mart may muddy the waters about what is and is not organic. Some are upset over the allegations and wonder whether other supermarkets will take steps similar to those alleged. “A huge amount of work went into coming up with a standard of quality in the organic industry,” says Randy Lee, CFO at PCC Natural Markets, the largest co-op operating in the U.S., which runs eight stores in the Seattle area. “If these allegations are true, then it very easily erodes those standards and comes with a significant business impact on other retailers that have higher standards.”

The watchdog group that prompted the Wisconsin investigation is called The Cornucopia Institute and has been active in what it calls “family-scale” farming. It has produced photographs of items that are not certified organic or are only partially organic that appear on shelves at Wal-Mart with banners or signs that say “Wal-Mart Organics.” The photos from Cornucopia show items that could be easily mistaken for organic. Many have descriptions such as “all natural” or “natural,” including Stonyfield Farms All Natural Yogurt and Florida Crystals natural sugar.

Still, even though an organic Wal-Mart apple or bag of lettuce mix would be produced in enormous commercial operations, it would still not be as input-intensive as conventional large-scale farming. And given the scale of McDonald’s and Wal-Mart, that’s a lot of fertilizer and pesticides not being applied.

Simply put, Wal-Mart’s potential influence is too large to be ignored. Wal-Mart is the world’s largest largest public corporation by revenue, and the largest private employer. In the U.S., Wal-Mart sells 20% of all groceries, 22% of toys, and is the largest private user of electricity. Due to this mind-boggling scale, even small changes by Wal-Mart are magnified to have a big effect.

A 2006 Fortune article describes Wal-Mart’s various efforts to go ‘green.’ These environmental initiatives, launched in 2005, didn’t grow out of a sudden concern for the environment. Rather, the company faced serious business and PR problems, including a class-action suit alleging sex discrimination, a damaging report showing that Wal-Mart paid 30% less to insure its workers, and millions of dollars in fines for violating air and water pollution laws.

A meeting in 2004 between Conservation International, Wal-Mart’s CEO Lee Scott, and Rob Walton led to a simple conclusion:

“Wal-Mart could improve its image, motivate employees, and save money by going green.”

Wal-Mart’s own efforts, from slimming down packaging and reducing gas used in transportation, have a huge effect due to the enormous size of the company.

“Wal-Mart installed machines called sandwich balers in its stores to recycle and sell plastic that it used to throw away. Companywide, the balers have added $28 million to the bottom line.”

However, the most important and interesting of Wal-Mart’s new environmental initiative is it’s role as a major intermediary between manufacturers and consumers. As the Fortune article points out,

If Wal-Mart influenced the behavior of a fraction of its 1.8 million employees or the 176 million customers that shop there every week, the impact would be huge. And because of the extraordinary clout Wal-Mart wields with its 60,000 suppliers, it could make even more of a difference by influencing their practices.

This is why Wal-Mart’s eco-initiative is potentially more world-changing than, say, GE’s. GE sells fuel-efficient aircraft engines and billion-dollar power plants to a few customers. Wal-Mart sells organic cotton, laundry soap, and light bulbs to millions. When shoppers see a display promoting “the bulb that pays for itself, again and again and again,” they’ll be reminded of their own environmental impact.

By buying CF bulbs they’ll also save money on their utility bills, leaving them more money to spend at, you guessed it, Wal-Mart. The bigger idea here is that poor and middle-income Americans are every bit as interested in buying green products as are the well-to-do, so long as they are affordable.

Plenty of places sell fair-trade coffee, for example. Only Wal-Mart sells it for $4.71 a pound. “The potential here is to democratize the whole sustainability idea–not make it something that just the elites on the coasts do but something that small-town and middle America also embrace.”

Maybe this will work, maybe Wal-Mart’s market saturation will enable it to preach the (consumerist) organic gospel to potential new converts. Or maybe Wal-Mart’s entry into the organic battle will result in a further dilution of the USDA organic standards, while continuing the company’s pattern of consolidation and vertically integrated manufacturing, continuing to squeeze out smaller producers and retailers. It’s hard to say, but I’m not willing to bet the sustainable future on Wal-Mart, whose goal, after all, is maintaining its business and stock price.

This is a very interesting, well thought out post. Nice job! On the one hand, it makes me want to run out and buy an apple at McD’s and some organic (really, truly organic) stuff at Wal-Mart.

Conversely, I also don’t want to encourage the production of only one kind of apple, and I’m loathe to fund Wal-Mart and it’s town-wrecking, state insurance-grabbing, sexist, and generally evil practices in any way, shape, or form.

But I can’t afford the fancy schmancy, trendy organic stuff you can buy at Superfresh for twice the price of the regular product.

What’s a conscientious guy to do?

Pingback: Ninjas on the ‘Net | AMNP

Pingback: Equality of Opportunity Limited by Human Rights | P.a.p.-Blog | Human Rights Etc.

Pingback: Please address the whole problem « Material Innovations